Coldchain is a phrase increasingly prevalent in the British beer industry but what is it, does it really exist, and is it being used correctly? Yvan Seth from Jolly Good Beer takes a closer look.

Coldchain distribution is nothing new – you see refrigerated lorries and vans on UK roads all the time. It is used for many food products – often as a serious matter of food health and safety, but also to preserve the quality of fresh produce.

What it means simply is that the product being distributed is kept chilled all of the time including transport links. This is what makes it a “chain” – every link is chilled. If you remove the refrigeration from one of those links then you don’t have a chain any more. The important thing about the chain is that it should be connected up all the way from the producer to the consumer (see below).

The Coldchain

Brewery Coldstore @ 4°C

⇒ Transport @ 4°C

⇒ Distro Warehouse @ 4°C

⇒ Transport @ 4°C

⇒ Retailer Coldroom/Fridge @ 4°C

⇒ Consumer

Why 4°C? At the most basic level the choice of 4°C comes down to food handling standards. The fact is that there is simply a lot of existing infrastructure and equipment set up for this temperature – “fridge temperature”.

I tend to regard our target storage temperature as “circa 4°C” and know a few cases where 6°C is used, and know a few breweries using 3°C for coldstorage. As 4°C is common for food storage it is also the temperature which most study and literature will refer to – such as “Freshness” by Dr Charles Bamforth.

In “Freshness” Dr Bamforth refers to the work of Swedish chemist Svante August Arrhenius that relates temperature to chemical reaction speed — and for beer uses a 3x faster reaction time for every 10°C temperature increase.

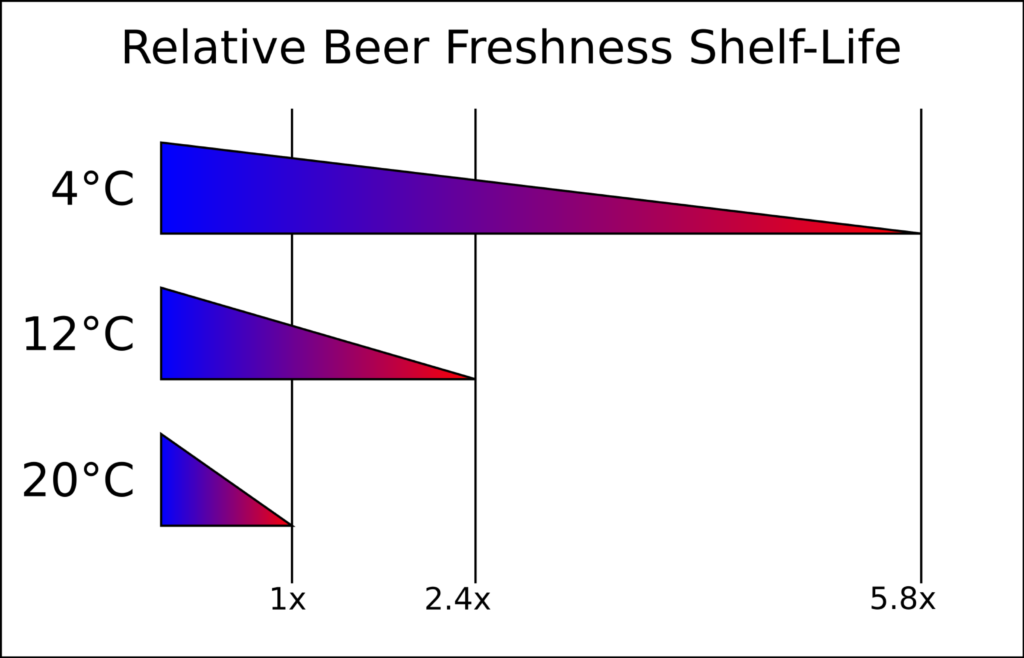

If you fit a curve to this trend and interpolate for 4°C versus 12°C the result is that at 4°C changes ought to be slowed down by approximately 2.4x – and versus 20°C this is 5.8x. In my own testing with 1-month changes in beers across 4°C, 12°C, and 20°C there was often a notable flavour difference between 4°C and 12°C for pale beers after just the one month (this is an experiment you can try at home!)

Of course the changes in a beer are on a continuum – unlike the general public view of “best before dates” being some sort of quality cliff-edge. The 4°C sample tasted fresh, and the 12°C notably degraded but quite drinkable, at 20°C it had become something I called “onion water” (the beer I have in mind here was a mid 4% pale dry hopped “session IPA”.)

In the associated diagram I have used the Arrhenius equation to show relative shelf life at 4°C, 12°C and 20°C. Beer aging is a complex and many faceted chemical, and biochemical, process — the key observation is the exponential nature of the rate of chemical change versus temperature.

Another way to think of coldstorage is as preventing heat exposure. Every bit of additional heat a beer is exposed to will push its chemical reactions a little further along that taste spectrum from “fresh” towards “stale”. By coldstoring beer we reduce this exposure and prolong the “fresh” life of the beer.

In the UK coldchain does not really exist for beer. There are a handful of cases where breweries both large and small have chilled vehicles. Stalwarts of British cask ale Timothy Taylor has curtain sided lorries with chiller units. The complex flavour nuances of traditional cask benefit from coldchain stability, not just the latest NEIPA juice bomb. And when Iron Pier brewery bought a dray van they took the plunge on getting a properly refrigerated vehicle. But these rare cases are an exception to standard UK practice.

Things get worse when you look at the wholesale distribution tier of the beer industry in the UK. Most distributors rightly have some cool-storage for cask ale, especially the larger well established ones. However there are many small distribution businesses, and surprisingly some large ones too, that don’t even have this for cask. It’s entirely the norm for all keg and smallpack beer to be kept at ambient temperatures.

I learnt this after I started my own distribution business. I started out by talking to brewers and asked them how I should do things. Every single one of them said I needed to get coldstorage for stock. So back in April 2014 that’s what I did – and that’s where Jolly Good Beer started. It wasn’t until months later I began to discover that what I was doing was unusual.

This put me on a path of promoting this missing link in British beer quality and ultimately to trying to achieve real coldchain for beer. The choice was to promote doing it right, or stop doing it right – because unfortunately the higher cost overheads make it a competitive disadvantage if the difference is not understood.

Coldstorage is not coldchain however – it’s just a link needed to create the chain. To achieve a chain we all need to move to refrigeration on the road as well as at brewery, warehouse, and retail.

A serious issue

There’s a combination of lack of knowledge and inertia. A lot of the problem at the retail and distribution level is simply a case of not knowing any better. Historically UK keg and smallpack beer has been predominantly the domain of stabilised products with simple flavour profiles — pasteurised and sterile filtered lagers for example. Even these beers are not immune to the depredations of time and heat, but a lot of work has been put into extending their shelf-life. I don’t think I need to convince brewers on the technical issues of beer stability – but if you’re unsure then look up the work of Dr Charles Bamforth, for example in his books “Freshness” or “Beer: A Quality Perspective.” These should both be mandatory reading.

It’s not the brewers who need convincing – it’s everyone else. A common sort of challenge I hear is “everyone else is doing it this way, why should I do it any differently”. Which is a sort of defeatism really. “Why try any harder?”

If we all took that attitude, where would British beer be now? (See also: food and coffee.)

The fundamental problem is that doing beer better costs more money. At retail the start-up costs and running overheads of a warm shelf are a lot less than a fridge. In distribution a large shed costs a lot less than a large coldstore. And if you’re already operating with beer at ambient, it is a big jump to upgrade to full coldstorage. Significant inertia exists within the established retail & distribution sectors — which is why most of the fully chilled operations in the UK are new businesses.

I know many great breweries who really care for the beer they produce and have full cold-storage at the brewery… when traveling around the country I am often saddened to see their beers sat on a shelf in an 18C room – heated in winter, not cooled in summer. Kegs under a counter or in an ambient back room, often actively being heated by a nearby integral flash cooled. It’s a sorry state of affairs. (There are also very good business reasons to do keg dispense better in terms of yield as well as quality.)

Where does the responsibility lie

Everyone in the chain has a part to play – everyone needs to really care about getting the product to the consumer as good as it can be. This includes the consumer! In his book “Freshness” Charles Bamforth states “Ultimately, substantial responsibility lies with consumers if they are to enjoy a beer with the characteristics that you expect them to appreciate”. The phrase “vote with your wallet” comes to mind – although how do you do that without retailers to buy from who take beer quality seriously? I firmly believe this is a natural result of caring for beer better and businesses that take quality seriously will benefit. So what can we do to even give consumers access to the better option?

One approach is to encourage better practices and push that message whenever possible — this very article for example. The use of good marketing, with the right amount of education. BrewDog have done the UK a fantastic service by educating many bar staff to Certified Ciderone® level – arming them with a degree of beer quality knowledge practically non-existent at retail level before.

Interestingly this meant enough knowledge to realise that BrewDog’s own bars and processes were not equipped to US quality and coldchain standards. It’s a powerful indirect endorsement of everything UK coldchain advocates been doing, that BrewDog is now rolling out chilled central warehousing and properly chilled direct-draw dispense in bars. Ultimately we’re all taking lessons from the top standards of the American craft beer industry.

When you own the whole process from brewery to bar you can properly solve these problems. What about all the independent operators?

That’s where the brewers come in and ultimately the responsibility for their product rests on the shoulders of the brewers. It’s massively in their best interests to encourage better standards to ensure their beer reaches the consumer at its best. The better a beer is the more consumers will come back to it – and to your brand. Ultimately this is a matter of brand protection for the long term. It can only take one bad beer to drive a customer away from your brand forever – how tragic it is when fantastic beer is brought low by bad keeping.

So what now?

Right now there’s very little chance you can have your beer distributed via a coldchain. Typically beer is moved around the country by ambient pallet networks and vans. Breweries need to encourage better practices – and give recognition to businesses that take this duty of care more seriously. They also need to bite the bullet and plan for investing in refrigerated vehicles and shipping. Take the case of Gravesend-based Iron Pier brewery – unwilling to compromise, they acquired a refrigerated van.

“For us refrigerated delivery was something we knew we wanted to do from day one, and it will become more important as we grow and as our delivery area, and therefore transit time, grows. We try and control every process we can in the brewery to ensure consistency batch to batch, so I just see controlled temperature in storage and delivery as an extension of that. It’s effectively a chain of custody, we’ve treated this beer as well as we can, and we would like to expect the same from the publican.

“In the keg market we see a lot of places with kegs at room temperature, often under the bar, and just running through a flash cooler of some kind. That beer is going to age so much quicker than even a beer kept in a regular 10c cellar, let alone if it was kept at 4c like some of the direct draw systems. Any instability in package is going to show up much more quickly for these people than someone with a cold cellar. Refrigerated delivery for us is about taking the best care of our beer, but also setting an example to our customers of how they should be looking after beer,” explains James Hayward from Iron Pier Brewery

I think this is key all the way down the chain. If you’re delivering beer “warm” to distributors, then why should they see any reason to do better after that point? If you’re delivering beer warm to retailers – same again. At Jolly Good Beer we have convinced several trade customers to improve simply by the fact the beer we deliver arrives cold and it feels somehow wrong to then let it warm up. But ultimately a larger industry change needs to come top-down from breweries.

That doesn’t mean the rest of us should sit back and wait for them mind – at Jolly Good Beer we’ve started working from the middle to implement coldchain where possible, having deployed our first refrigerated HGV this March. Coldchain is an achievable goal.

One of the most shocking things to me is that in five years of trading I have only ever had a single brewery request a site inspection, albeit many others have visited on my own invitation. I would welcome more inspections with open arms. If I was a brewer I’d be much more interested in how my beer is being cared for down the supply chain than seems to be the norm.

There is probably call for a brewery-backed scheme to verify supply chain standards. A more modern-beer targeted version of Cask Marque? There’s nothing like getting a check-mark of approval to motivate people to up their game.

A changing landscape

It’s pretty much coming hand-in-hand with industry adoptions of other aspects of American “craft beer” practices. The popular new beer styles are so sensitive to time and temperature that awareness of the need for better practices is growing – and I’m talking session IPAs and West Coast IPAs, not just NEIPAs. It’s all starting off in ones and twos. One of the first fully chilled retailers to be fully coldstored was The Stoneworks bar in Peterborough – somewhat unsurprisingly one of the partners in this business is from the US. Steve Saldana looked around and wasn’t happy with what he saw so in opening the bar decided to do something about this.

“There was no other place doing it right. It angered me that when asking people why beer was being served this way (bad dispense) they said it was the best way and there were no other options… I wanted to prove them wrong,” says Saldana.

The bar is going strong, now well into its third year of trading, and I use it as a prime example of good practice. This year, via Jolly Good Beer, they will start receiving beers from key brewers via a full coldchain on a regular basis – I believe this may be a UK first.

I have started building a map of UK “coldchain-ready” retailers. I tried this two years ago and decided a map with just 3 pins on it wasn’t much use to anyone. Today, not including brewery taps, I am up to 9 – which is certainly an improvement but it’s a miniscule proportion of the total number of beer retailers in the UK.

The most positive thing right now is simply that people are actually talking about coldstorage and coldchain more. It is becoming “a thing”, per se. Our fellow wholesalers The Bottle Shop also moved to full coldstorage at their warehouse in 201X(?), and last year BrewDog announced they were moving their central distribution warehouse over to full coldstorage. Through the work of businesses like The Bottle Shop, importers Cask International, and ourselves we’re seeing more importance put on imports being fully coldchained to UK coldstorage facilities.

It is a bit of a joke that we don’t show British beer that same level of respect. It’s even reassuring, albeit disconcerting, that people have been caught out lying about having coldstorage and coldchain … it means the right questions are being asked, and those without the correct answer are feeling compelled to lie.

We have discussions in place to help four venues this year launch coldchain-ready, and a long-term goal of connecting up coldstore dots to form a chain to all these sites. My hope is we can encourage more people at all levels to move in the right direction, for the sake of awesome beer.

The future is brightly flavoured: the future is chilled.